Chapter Eight

Married life in Harpur St. – Stewart, Bertie, Louie, Duncan, Alice, Grace, Katie and Margaret born – Move to Peckham then Clapton – Scarlet fever, whooping cough, peritonitis etc

Things were not finished or in order for us when we reached Harper Street, and it much annoyed me, that we had to make one party so soon, but by degrees our rooms were finished and looked very nice. However, after a few months it was a trouble to us, always to be included in my Mother’s plans, and dependent on the hours and meals of others. Things became rather strained between us, Louie, I knew felt with us usually, but of course, could not say so, and we spent our first Christmas Day at Uncle John’s for want of a pleasanter invitation. As there was a prospect of our needing more rooms, we decided on fitting up a second kitchen for ourselves and having two servants and more bedrooms, this we did early in 1845, and after that, all went far more happily.

In the end of March, we heard that Stewart had suddenly left Calcutta, owing to his wife’s conduct, and was working his way home before the mast. This was sad news to us all. He arrived one Sunday morning, when I was alone, but Pears, my father’s old barber, had seen him first, and brought him to Harper Street, Stewart had known Pears all his life, as my father had helped him when young and he was always grateful to him. Stewart was in a most miserable condition, quite broken down, and it was a great shock to me to see him, really unfit to be in our home. By degrees he improved, and recovered his old tone, and was much with me, as we had been very fond of each other. About a fortnight after he came back, my first child was born on the 20th April 1845, on the same day as we had been engaged five years earlier. He was named Charles Stewart, and was always the most loved by his Grandmother and Aunts. We had rooms in Peckham Rye in the Summer, and my baby, was much admired at Uncle Charles’. In the Autumn we took him to Ramsgate for your father’s holiday. On Christmas Day he sat up in his own high chair, when we lunched looking sweet in a frock of cerise coloured Cashmere of which I now have a piece, after 52 years.

In May 1846 our second boy came, on the 29th, he was named George Herbert, after his paternal Grandfather. He was a strong fine child, and when three weeks old, began to scream or rather “roar” which continued for seven months, it was a terrible trial, his poor nurse was constantly stopt in the street by enquiries as to what was wrong. We took him to Dover where my mother was, but had to leave as people could not remain in the house. Then we took him on a visit to my Uncle Wicksteed at Leatherhead, but they could not bear it. He slept well, but if awake roared incessantly. Suddenly it ceased, and I doubt if he ever cried again!! he always amused himself, and was a happy child. People said I thought more of him, than of Stewart, but I always felt so much was done by my family for Stewart, that I had to do more for Bertie. Stewart was a delicate, highly nervous child and less easily managed; he could read when only three years old. I nearly lost him when he was two, owing to his having had some tincture for a cough, given against my wish by Mrs. Pulley, it affected his brain, and but for Mr. Bean’s happening to call in Harper Street, when the child was lying on my lap, and at once putting some calomel on his tongue, he would have died. After that, I never allowed quack medicine to be given.

At the end of 1847, after a very hot summer, which had tried me as we had been in London, only spending a fortnight at Grove Hill our first daughter Mary Louisa was born on the third of November, and before Christmas we had to leave Harper Street, the lease having expired. We had a fancy to live at Peckham, our old place, and took a nice house in St. Mary’s Road, near New Cross. But it was a changed place, and people, from what it had been in our youth, and we did not like it. After a few months, the flooring gave way, and it was found that dry rot had destroyed the timbers of the house, so we had to leave. Uncle Charles was very anxious we should live at Clapton, near my Uncle John, as we had it in his power to help, and was very fond of us. Small houses were scarce then and we had to take some rooms for a time, at last we found a small house on Dalston rise, close to the downs, which the landlady added to and improved.

At that time March 1848, all Europe was in the utmost confusion. The French had risen against their King, Louis Philippe, who was forced to escape with his family, and in great risk, from Paris, and take refuge in England. Claremont belonging to his son-in-law, the King of Belgians was assigned to the French royal family. The young Duchess of Orleans, whose husband had been killed earlier, in jumping from his carriage, took her two little sons into the assembly, and appealed to the nation on their behalf, but uselessly. Royalty was for a time abolished, and a Republic formed.

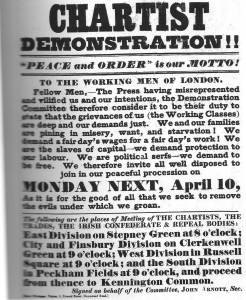

In England this wave of rebellion had excited the lower classes, aided by the distress in this country, and a body of Malcontents, Chartists as they were called, caused the utmost alarm. London was prepared for defence, our Queen and her family were urged to leave Windsor, troops were ready to guard all public buildings and places, and the mass of gentlemen, were sworn in as special Constables. Among these was Louis Napoleon, who had lived quietly in London since his escape from Ham, and who in a few months was President of the French Republic, and in 1851 by the “Coup d’Etat” Emperor of France. But the riots expected here fell flat, though the people were all in a panic, the government had made such powerful arrangements, very quietly, that the project of rebellion failed. The Charter was sent in cabs to the Parliament, only a few thousands met at Kennington, and ere long “The Chartist riots” was a scare of the past.

Our small rooms in Clapton were uncomfortable and as our house could not be ready till July, I joined my mother and sisters in a house at Tunbridge Wells for a time.

I have not spoken of my dear sister Louie’s engagement in 1846 to an old friend Mr. Hoare, his brother had known us for many years having been a school-fellow of my brothers’ at Uxbridge and came often to our house after leaving school. Tom Hoare was a quiet, shy young man, and we once thought he admired Louie. But his brother only made our acquaintance in 1840. At first none of us liked him, he was rough, and of a different type, however, he became our great friend, and with many faults had unbounded sympathy and kindness of heart. He was not a successful man like his brother, and though a friend of my husband, we were surprised and indeed sorry that Louie cared for him. In every respect, they were so unlike that it seemed very uncongenial. He was godfather to my Louie so I kept my three children at Summer Vale more than two months, but it was inconvenient for Charles to come, so I was glad when the alterations at our little house on Dalston Rise were ended, and we went back in June. There was not much spare room, but it was a convenient pretty home, with a garden open to the Downs and plenty of fresh air. We had relations near in Clapton, Uncle and Aunt John Pearce, Mr. and Mrs. Greenwood. The Blaxlands and others, very often I drove with Aunt John to see our relations at a distance, and many of their friends, soon became ours also.

I was much at home having only two servants, and three children. In November my mother was at Hastings and for the first time, I left my baby Louie, taking Stewart with us to stay with Mother. I was looking at her in her Nurse’s arms, and did not notice my Stewart’s hand was on the door of the omnibus, when the man slammed it, and shut in his little fingers. He gave one shriek and then had to bear the agony of forcing the door to, in order to unlatch the handle. I had no remedy, save to put his crushed fingers into my mouth, and I shall never forget, how the child only four years old, writhed with pain, and would not cry, it was dreadful. By degrees it abated, a gentleman in the omnibus heard me say he was going to the sea, took out some money, and told Stewart he had behaved like a hero, giving him money to buy a spade and bucket. But the shock tried my boy much, and he was very poorly. We came home soon, Stewart remaining with his Grannie and Aunts till Christmas. In the early Spring of 1849 Bertie developed Scarlet Faver, which Stewart and baby also took. Bertie was very ill. Our nurse left in terror, and my sister Louie came to help.

In 24 hours she was laid up with it, and we had no help but our general servant and an old nurse from the alms houses; it was a bad time, but mercifully all recovered. Our good servant actually had the fever and never gave in, or failed in her assistance to us.

I suppose during that illness, Louie had leisure to think more of her engagement to John Hoare, for as soon as she recovered she wrote in terms of great sorrow, to cancel the same on the plea of unsuitability of habits. We were all very thankful, yet Mr. Hoare remained a dear friend of my husband and myself to his death in 1867. In July 1849, Amy was born, and in August we shared a house at Broadstairs with my mother. Whilst there, Mr. Woolley, my father-in-law, was suddenly ill. I came to London with my baby, but never saw him again. I was very fond of him and always received from him every mark of affection. We followed him to his grave, in Abney Park Cemetary and then returned to Broadstairs.

Stewart often staid with his grannie who was very fond of him. In September 1850 Charles and I went to Swansea in South Wales to stay with Mr. Hoare, who then owned the South Wales Brewery. We met many friends of his, and had Picnic parties to the Mumbles, a beautiful place on the shore. In climbing up a rock, to which Mrs. Street and I had scrambled up, John Hoare received the damage which ultimately caused his death. We went to Chepstow, Hereford and Worcester, on our way to Birmingham which I thought very dingy and smoky, to Manchester, when we saw Mrs. Gaskell, who lived next door to Mr. Williams where we visited. Mrs. Williams was Aunt Charles’ sister, then to Liverpool, where I was very unwell, had caught some sort of eruption at a Hotel. For the first time we saw my brother John, since his imprudent marriage in 1848, to a Miss ? a Roman Catholic in Glasgow, this step cost him his post in the Electronic Telephone Co., he had two children then, and we were helping him to go to Melbourne.

In the Spring of 1851, we required more room, and with some regret took a home in Clapton Square. It was nicely done up for us, and we were busy adding to furniture as we wanted to be settled there in May. Half our goods were removed and I had been in London shopping, when rather unexpectedly on Ash Wednesday, March 5th Duncan and Alice arrived on the scene! It was awkward, I had seen my mother on the previous day, and she was so horrified at hearing of twins, that she started off at once to her house at Tunbridge Wells. But no sooner was she in the train, than she felt equally shocked at going away, from me, when I was in trouble, and so returned by the next train, come down to Dalston Rise, and carried off the children and their nurse to Tunbridge Wells. I did not at all enjoy my experience of two babies in a house from which half the furniture was removed and really little comfort for nurse or children, they were very delicate, especially the girl, and at the end of ten days, they were baptised by the Rev. A. Gordon. For many weeks and months we were very anxious about Alice, but I think now, Duncan was really as delicate. At three weeks, all was in nice order in our new house, and Aunt John drove us there, and soon after nurse Curtis and the other children returned, we had an under nurse, and were comfortable with four servants but six little ones under six years is a burden.

On the 1st May of this year 1852, the famous Great Exhibition in London was opened by H.M. The Queen. It was the wonder of the age, and entirely the idea and work of the Prince Consort. Since then Exhibitions have become universal and frequent, but this novelty caused much excitement. It was opposed, and said to be impossible on all sides, and pronounced to be a folly and certain failure. No one however, who on May 1st 1851, was present at the opening of the “Great Exhibition” at Kensington, could have denied that it was aught but a complete triumph. It was opened by the Queen and Prince with their four elder children, The Duke of Wellington, who had then but another year to live. Crowned Heads, Nobles, Artists, foreigners from every known country, and thousands of English of all ranks were there, it was a place bearing some aspects of a gigantic hot house and others of a huge bazaar. On the stalls were heaped the products of every nation, from the “Koh I Nohr” to a tin tack, from the most gorgeous Eastern Manufacture to a piece of tape, every kind of machinery in working order, all that could be made or carried was there at its best. Altogether, it was a union of all people, places and things in the world.

My husband and I went to see it taking our two boys. Bertie evinced then his genius for collecting and to my horror, displayed to me, with glee, a piece of an earthenware broom, which he had broken off a Chinese “bas relief” to take home for a keepsake. I fancy he is the only person who did such a thing, and it spoilt my day, for I fancied perpetually this relic in my pocket, would be detected.

We were very comfortable in our new home in Clapton Square, having more room and another servant but our old garden at Dalston Rise was a loss. Not long after we went there, our friends the Blaxlands took the next house, whence out intimacy with them. Mr. Blaxlands was a distant connection of the Woolley’s; his wife and I had been playfellows when quite young. For some time I taught the two elder boys, but in 1852, April, my husband had small pox, not severely, but it prevented me from being in the family for a time, and then he and I went to Brighton, Stewart was 7, so went to the Grammar School, and Bertie to Mr. Newcome’s being only six.

On July 30th our little Grace was born. I was ill for some time, and for change went to my Aunt, Mrs. Wicksteed at Chislehurst taking baby, Mrs. Noakes my nurse and Amy, who was my Aunt’s godchild. Not being better, I took baby and Mrs. Noakes to Brighton where I quickly gained strength.

In the November of this year 1852, the Duke of Wellington died, I wished to see him laid in state, but Charles would not take me with him. It was fortunate he did not, for the crowd was terrible and had he been encumbered by me, would probably have lost his life. He was dragged under the barriers out of the crowd, almost senseless, his great coat was absolutely wet through from the state of the heat he had been in, there was a dense mist over the crowd from the heat.

In April 1853 my Stewart went to see the Houses of Parliament with his Grandmother and Mrs. Greenwood. Arriving down the stairs from the House, he suddenly fell lame complaining of his knee, for weeks he was confined to his bed. Dr. Little saw him, and said it was contraction of the muscles, and that he would be lame for life, a model of his leg was taken at much expense. Our doctor Mr. Complin being ill, his son Edward a student saw Stewart, and on careful examination, detected a large abscess under the knee pan. After a while, this was opened. It was great agony, but my boy was good, in a few days he could stretch out his leg, and all fear of danger ended. He always walked rather lame.

No sooner was he better than all the seven children had whooping cough. I never had it, nor did I take it then. Our sweet little Grace took the infection, but did not cough, from the first, she never cried or fretted, laid still on her pillow, slowly dying. On the morning of June 8th we saw her pass away, I think without pain. She was a lovely child, her features, hands and feet, were perfect. I never saw a sweeter face. Mrs. Lucas placed a bunch of lilies of the Valley in her clasped hands, saying they were emblem of her – 11 months old. When the children began to lose the cough, we all went to a house in Mortlake, in the midst of an apple orchard. No words can tell how I detested the place, it was a sunless Summer and the gloom with no outlook or view, dreadful. We came back in August, Katie was born in September 9th.

Our house was then so full, that we sent Stewart and Bertie to school at Mr. Altree’s Tunbridge Wells, where my mother had lived, she had removed to West Croydon in 1851. The boys were well cared for there, and well taught. I had the two elder girls Louie and Amy to teach, and there were then three younger ones, so I was relieved by the boys’ absence and I had more leisure for all the needlework. I never put out any clothing to be made before this year, when the elder boys had heavy cloth tunics and trousers.

I had forgotten that this year 1853 my sister Louie who only called at the door to ask after those who had whooping cough, actually caught the malady, and was quite ill with it. My mother and sisters then went down to Rousley in Derbyshire, close to Chatsworth where they spent the Summer in a nice farm house, they also were near Mr. Allcard’s Country House, he was a great Florist, and had gone there to be near the Duke’s head Gardener Joseph Paxton, who had been knighted at the opening of the Great Exhibition in 1851, in which he materially assisted as regards the building of the “Glass House” and grounds. His daughter Victoria married George Allcard.

I think we must have sent the two boys to school at Tunbridge Wells in the Spring of 1853, as I recollect Stewart was only three months at the Hackney Grammar School in 1853, before his knee was hurt, and Bertie was a year at Mr. Newcomes. I think, therefore, after Katie was born in September, /53, they must have gone to Rose Hill, as then there were five in the nursery, and I had to begin to teach Louie and Amy. The two boys had been a pleasure to teach, they were very quick, when they began French, they were not attentive, so I used to make them sit up on their high chairs whilst I read aloud an amusing story in French, if they sat perfectly still during the reading, I then gave them a free translation in English.

In 1854, we thought of removing to the forest as we were cramped for room, and should have then sent the elder boys to Mr. Gilderdale’s but there was no railway from Walthamstow to London, and houses were scarce, so we waited. On November (the 9th) our daughter Margaret was born, she was delicate, and we had her baptised hastily. For many weeks I was kept in my room with illness, and a wet nurse was had for the baby. On the 15th of January 1855, I was able to go to Church, my sister Louie being with me.

I had not left my room before, and was very weak. Charles was away, and in the evening Louie was very unwell, and my monthly nurse, who was still with me, put her into a hot bath in my bedroom. She became much worse, and was lifted into my bed, Doctors came, who thought her in imminent danger, and I spent that night in running about, when in the morning, I had been an invalid.

Early we sent to Croydon for my mother, and to London for Dr. Addison, and by Louie’s wish to Mr. Bean our Uncle at Camberwell. They met in consultation, and Louie asked Mr. Bean to return to tell her if she were dying. I was by her, and shall never forget my sensation as he came into the room, and pronounced the verdict… death………….

She asked for Mr. Gordon to administer the Holy Communion which we received, together, and Mr. Gordon left. After he went, she turned her face to me, and said in a whisper, “I feel sure dear I shall recover.”

The attack was Peritonitis of a most severe kind, and for days we doubted the result. She was in our bedroom for six weeks but did rally. All our children were dispersed to different friends, only the baby and her nurse left. In April Louie was taken to Croydon in a carriage, and we returned to our room and once more collected our scattered family. But peace was short lived. In a week or two the twins and Katie were taken ill with Scarlet fever, the nurse who had been with Louie, came back to nurse them, and we had to undergo for many weeks, a system of quarantine, or course, no one risked coming to see us, though the patients were isolated; only Mrs Bernard Lucas, met me daily out of doors. The elder girls had a daily governess who left directly, so I had them again to teach. The children recovered well, we had sent baby and her nurse to Woodford Green from the first, and as soon as the three could go they followed. There were no drawbacks with the twins, save that Alice made Duncan swallow a brass knob of the blind, which alarmed us. Katie had dropsy.

Continue to Chapter Nine: Move to Upper Homerton – Frank, Basil, Honoria and Janet born – The Croydon wet nurse – Move to Grove House – Typhus and the drains

Email link

Email link