Chapter Seven

Death of Mary’s father – Theft and court case – Paris – Move to Tulse Hill – Marriage

On the 18th of December we were all looking gaily to Christmas. Charles was to take me to a dinner party at his friend Mr. Harrison, in Sussex Square. My Parents, Louie, and William were dining with Mr. Mill Pellatt at Stoke Newington. The weather was very severe, and my father forgot to put on his great coat before getting into the carriage. We all reached home about the same time, and sat round a large fire in the morning room, full of life, fun and jest, until father sent us unwillingly to bed.

I came down on the 19th. to make breakfast as usual, for our large party, when father came slowly into the room and dropped into his arm chair. I said, “You are ill, Papa, what is it?” and he replied indistinctly that he was very ill. My mother breakfasted always in bed, but I ran up, begging her to get up at once, which she did greatly alarmed, and we helped our dear father upstairs and into bed. I remember mother mechanically folded up all his clothes and put them in his wardrobe. We had sent for Mr. Gaselee who was near, and to Camberwell for Mr. Bean. When they came, they said it was an attack of Erysipelas in the throat from the chill on the previous night, and that his feeble health and stoutness rendered the pressure on the brain very serious. Dr. Cobb was then sent for. I waited outside the bedroom door to hear his opinion when he left, but he answered my distressed questions so roughly that I turned away into another room. When he went down with Mr. Bean he said “I am afraid I answered that poor girl like a brute when she spoke, but I could not tell her that her father was a dying man.” Mr. Bean told me this, and it shows how easily misunderstandings arise.

Sunday passed in great anxiety. He was rarely conscious. On Monday some improvement, and when Dr Cobb had seen him, he asked for me, and said there was a hope. Mother and I with Charles, were with him at 6 p.m. and only went down to dinner, leaving Chase, our nice maid in charge. I wanted to stay, but was not allowed and shall always regret it, for I was called up hastily, as father had asked for me, saying something about my eldest brother Stewart. When I ran up, the gleam of consciousness was over. We went to bed after Mr. Gaselee had seen him. At about 3 a.m. mother woke me, I was soon by his bed, holding a bottle of salts for him to smell, hot mustard poultices were on his feet. I saw Mr. Gaselee take my mother away, and lead her from the room; then he returned, took away the salts from me, saying, “he is at rest, Miss Pearce, go to your mother.” I went into the morning room and mother sat on the sofa, absolutely stupified, and I remembered how we had been so merry there only four days ago, and then, all were assembled except the dear father who had been only too indulgent to us all. Soon Chase came, and urged mother to go to bed in the spare room, she was passive and neither spoke nor cried. It was awfully cold, and my brother, Charles, Louie and I went into the Clerks Office, in which a huge fire was burning. It seemed further off from our trouble than the usual sitting rooms.

Our man as soon as it was light was sent off to Peckham Rye, where Uncle and Aunt John were staying at Uncle Charles’. By 8 o’clock we all went up to breakfast, or to try to take some, and soon my Uncles came. William never spoke, he was huddled up in father’s great chair, brokenhearted. He was his favourite son. Uncle Charles was full of grief, but always kind, whilst Uncle John was rigid. He was very fond of father, but often harsh to him, partly because he and mother were not very cordial, and he considered, she led my father to be more expensive than my Uncles thought right, when his health was so bad, and his family large.

Everything came to be done by me in the house. Mother did not care to leave her room or speak. Had not Charles been always ready to help me, it would have been hard work to arrange all details for mourning, etc., by a girl of 18. On Christmas day we induced mother to dine with us, a sad party in the room he had occupied a few days before.

“The family vault in Bunhill Fields, E.C.” where Mary’s father, uncle Charles, baby cousin George and aunt Elizabeth are buried.

The funeral took place on December 27th. It was necessary to ask for permission to keep Swithin’s Lane clear, in order to have space for the Hearse and Mourning Coaches, all with four horses to come down a narrow lane. Old Mr. Watkins who had married my parents, read the last service over our dear father, in the family vault in Bunhill Fields E.C. On Sunday Mr. Watkins preached a funeral sermon. It was a day long remembered by many, the cold intense. At 6 a.m. all London was roused by the most awful thunderstorm. The crashing of the thunder was terrible, many thought the end of the world had come, and poor mother who was always afraid of a storm cried out that the end had come and she should be once more with father. It was bitterly cold when we went to St. Swithin’s Church and of course, we were much affected, so that on coming into the street, the cold seized Louie’s face. By the evening she was very ill, and had an attack of erysipelas in the head and face, so that for some time her life was in danger. All the beautiful long curls, which had grown since she cut off her hair, had to be removed, and her features were hardly to be distinguished. However by degrees she rallied.

We had another trouble then, all my mothers and our own colored clothing had been packed in boxes in a top room, and by some chance, one box was opened, and it was found to have been robbed. On examination many things were missed, and the cook and Dennis, the manservant were proved guilty. As my mother could not appear in Court to identify them, I had to go. It was not pleasant but Charles and four or five of our friends went with me. Sir Peter Laurie was on the Bench and when I was put into the witness box, he as was his custom, began to use very rough language. When the Book was handed to me for my oath, I took it. Of course I had a crape veil over my face. “Put up that veil”, he said, “so that I may see all you do.” A murmur went round the Court, and Mr. Brown the City Remembrancer who knew us, leant over to Sir Peter, saying “Do you not know that young lady is Miss Pearce, daughter of Mr. Stewart Pearce, who died lately.” At once Sir Peter stood up, expressed the utmost regret that he had not been informed of this, and begged me to leave the witness box and take a seat on the Bench. To this politeness, I replied by saying I preferred to remain where I was, during the examination. I had no more rudeness to complain of, and left the Mansion House with my “body guard”. The servants were both found guilty and some of the valuable things, shawls, furs, etc., were recovered.

In January 1841 my brother William went out to the Swan River in Australia, to which place Uncle John Pearce had secured him a post as a Civil Engineer at £400 a year. The income was large, but all the necessaries of life were so costly there that it was really hard to live. Butter, I recollect, being 4/6d per pound. William was always so full of life and fun, we missed him sadly. The heat that Spring was very extreme, and by May we were all unwell, so mother took a house at Mortlake, near Richmond, for the Summer. I remember as we drove to Mortlake, all of us wearing gowns covered in crape to the waist, we actually opened the doors of the Coach on both side, to obtain air!

In January, I forgot to say, my Uncle John Barton returned from Peru, S.A. where he had been since 1822. His wife was staying in Swithin’s Lane with us, and we had all gone to bed. I was sleeping with her, when we heard loud knocking at the house door, and Uncle had come up from Liverpool with his brother, Jonathan, two days before he was expected. All the household got up, and it was very strange. I thought of that night in December when our dear father past away, but this was all excitement, not sorrow.

We had a nice Summer at Mortlake, all our friends liked to come, as we had a good garden. In July we came back to town and mother began to look for a house near London as now father was gone Uncle John thought it not well, we should continue to live in the City. Uncle and Aunt John went to Margate, and asked me to go with them. Charles also spent his holiday with us. After we had been there a little time, Uncle proposed to take Aunt to Paris, and I prepared to go home, but to my amazement he included me in the Continental plan.

In 1841 no railways existed I believe in France. Certainly there was not one from the Coast to Paris, so that travelling abroad, had not become the ordinary habit, but few people of our class had a chance of going abroad for a short holiday and there was a hope of adventure, and entire novelty. That a girl as I was, should be invited to visit Paris, under the auspices of a man like my Uncle, who was a Government Employee, was very exceptional, and I was much envied. I was sorry to leave Charles, but my intense delight in the prospect of actually seeing Paris, and visiting every place, which love of reading and of French History, had made familiar to me, left me, I fear little room for any regrets.

In the middle of August, Uncle and Aunt and I left Margate for Dover. Before starting, my kind Uncle Charles sent me a cheque for £5, to spend in Paris. We slept at the Lord Warden Hotel, and the next morning, in heavy rain, and a strong gale, steamed over to Boulogne. Our travels did not begin brightly, but nothing damped my spirits, and when, out of 60 passengers, only Uncle and I were quite well, I felt triumphant. Lord Mahon, the new ambassador to Vienna, with his wife and servants, and one of the Rothschilds were there. Lord Mahon never moved, wrapt in a cloak, he cared for no one, and only cried continually to the Captain or a Sailor “How long will it be?” Poor Lady Mahon was really ill and helpless, not a servant could or would attend her. At last my Uncle went to offer his aid, which she thankfully accepted. He almost carried her across the deck, to where her carriage stood, placed her quite comfortably in it, with all needful appliances, and, at all events, gave her the blessing of solitude. We reached Boulogne late, and the tide would not allow of our steamer entering the Harbour, so for hours she lay, rolling outside. It was dreadful to hear the groans of the passengers.

At last, about 5 p.m. we landed, after 7 hours passage. I still remember the excitement with which I saw all the Normandy fisher wives in their bright costumes, blue skirts, scarlet stockings, and high snow-white caps, and big gold earrings and chains. We are used to this coloring now, then it belonged to France, and was a new experience, and the noise of the chattering in French around me and the difference in the look of houses and surroundings, almost distracted me. At last we reached the hotel du Nord, where we were to sleep, and again all was new. The polished floors, great glasses and clocks, high windows and the curiously furnished bedrooms only added to my delight. The rain was so heavy Uncle would not take me out, but I could not sit still. He went away, and returned bringing me a book, “The Idler in France”, by Lady Blessington, (I have it now, 1897), and entreated me to sit down and read it till dinner time, which I did. My first Table d’hote dinner was an engrossing novelty, but now everyone is used to them. I slept well in my nice French bed, and in the morning, woke to find sunshine and a lovely August day.

Uncle determined not to post to Paris, which was rather expensive, but go by diligence. I doubt if any of my readers will know of such a vehicle, or if one may yet be found in France or Spain, in some remote spot, still free from trains. We had hoped to have places in the Banquette, a hooded seat on the roof so as to see the country but it was engaged, and we had three seats in the coupee, like a large coach. Those who had corner places did well, but mine in the middle was dull. However, I saw no troubles. The long roads of France, are uninteresting, but every now and then, a village, or a chateau enlivened it. There were four and sometimes six horses, rope harnessed, and a constant talk went on between the coachman and his team. At Abbeville we stopped to dine, I recollect there was a hugh spread of food, all different entirely from our English cooking, and splendid fruits. I had hoped to have time to see the Cathedral and more of the town, but we had to proceed. It was a terribly long journey of 15 hours to Paris, and I never left my seat all the time. When it was dark they let down from the roof, a shelf, on which I was to rest my head and sleep, but I never wish to go through that night again.

At 7, we were in Paris. All my misery was forgotten, and when I saw the site of the Bastille destroyed in 1830, and the ropes with lamps on them, across the street, on which the mob shouting “a la lanterne” had hung up so many poor wretches, I was unable to sit quietly and Uncle declared I behaved like a maniac but he saw I was happy. We drove to the Hotel Bristol in the Place Vendome (now always used by the Prince of Wales), but could not have rooms. They directed us to the Hotel at the opposite corner, (the square had corners cut off), in which Uncle took a beautiful suite of rooms au premiere, ante room, salle a manger, salon, and three rooms beyond for sleeping, all opening into a corridor behind. I never had such rooms again! We had every luxury in this visit, a carriage and pair of horses was always in the court yard of the Hotel, to drive Mrs. Barton and me to all sights or shops, but this was not how I wanted to see Paris. I longed to walk, to go into the Faubourge where the horrible drama of the Revolution had been played out, to the quarter “St Germain” in which were the palace like houses of the old French Aristocracy whose blood had saturated the open squares of the City, and stained the water of the Seine. Now this was not understood by my Aunt, who was very conventional, and my Uncle had many friends among French Officers, and could not give all his time to my romantic ideas, as he considered they were. In fact it was not romance, but my love for history which led me to desire to verify all I had read at home. I had to submit, but was allowed to go out alone, just round the Place Vendome and adjacent fine streets and shops.

One day the whole City was out to witness the King and his sons going out to meet the troops who had returned from taking Algeria, under the Duke D’Aumale and Prince de Joinville the two younger sons. The whole mass of soldiers were to return through the Place on which our rooms looked, led by the King, Louis Philippe and all his sons and Officers, a splendid set of soldiers, Cavalry and Infantry. Just as the troops were turning from the Boulevard into the Place, a man shot at the King. The roars and excitement of the mob was awful. I believe they actually tore the would-be assassin to pieces, and when the Cortege passed us and stopt a minute, the noise and acclamation were not to be described.

Seven years passed, and the French populace who had done this homage, would have murdered this King and his family, and drove them into an Exile in England where the King and Queen were sheltered at Claremont, and died there. Most of the Princes lived here and still do so, at least their descendants have homes here, the elders are dead.

We had a charming time at Versailles, sleeping one night in an old Hotel there, which had seen all the splendous and sins of the Courts of Louis 14th and 15th, and the fall of Louis 16th in 1783. All the floors were so polished it was difficult to walk safely. The bedroom with but a couch and easy chair, and washing apparatus, a glass bottle of water and a white pie dish for basin. All the world are now familiar with Versailles and its miles of pictures, among which the artist David, paints France as always victorious. But the German Conqueror by now ruled in its vast halls, in which he has received the title of “Emperor” from Germany. We also went to St. Cloud, a favourite of the old kings, before the end of the monarchy. It is gone now, levelled with the ground. The famous manufacture of China, a royal property, at Sevres, interested me much. I meant to spend some of my money in buying keepsakes there for the home people, but finding the cheapest cup cost three to four pounds my intention was abandoned. We had some of the French Officers about with us usually, and my Uncle gave very delightful dejeuners and dinners at the most renowned Restaurants in Paris, or at our Hotel. It was my first and last experience of the most delicious “Cuisine” and splendid rooms. Subsequent visits had been more carefully conducted but not less enjoyed. We went to one or two theatres but my Uncle did not care for them. He had to be in London by the 24th September for the wedding of Mr. Tyerman with E. Berkeley.

On returning to London in Sept, 1841, I found my mother had taken a house in my absence, at Tulse Hill, a new district about 5 miles from London near Streatham and Clapham. I was very vexed at her choice, a horrid little villa as they were all called, detached in a piece of ground not yet laid out as garden, no trees anywhere, all new half made roads. It was named Hanover Cottage after our dear old Hanover House, a most unworthy descendant.

We removed from St. Swithin’s Lane into the Villa in October. It could not hold half our belongings. Jane and I shared a bedroom twelve feet square, a similar apartment with a light closet as dressing room for mother and Louie. The rooms on the same floor were alloted to Mrs. John Barton who was to live with us on my Uncle’s return to Lima. The attics for servants and boys. Long narrow sitting-rooms, with windows at each end. How cordially I detested the narrowness of it all, such a great disappointment to us, who had hoped once more, for an old house and shady garden. Of course, too, all the other Villas were soon occupied but the inmates were not of the kind of society we had mixed in. Many were good, kind people, but we always felt a want. So 1841 ended in a dull uncomfortable loneliness, only brightened when our old friends came. This too was not easy, as no public vehicle then went beyond Brixton church, more than a mile from us, so were all the shops. My Aunt was then with us and by degrees we became used to the place but the house was so new and ill built, there was always some trouble.

In the Spring of 1842 it was proposed to build a church for this district, and all were interested in collecting money. for the purpose. People were not so overwhelmed by begging for charities, as they are now, and we collected a good sum. So Christ Church was begun. I never much admired it, though it was correct in architecture. The Rev. Wodehouse Raven was the first Incumbent, and our marriage on the 18th of July 1844 was the first performed in the Church. For a long time the road up to it from our house, was unmade. It was a dark and difficult walk in the Winter evenings.

I was ill in the Summer, and in September we all went to Brighton, taking my mother, and Aunt Ann Sherer with us. This was my mother’s first experience in railway travelling. We drove to Croydon to meet the train, taking our luncheon with us. The nervous condition of the two elders was really distressing. The train was so full, our party was divided, and to my great annoyance the mother and Aunt were hurried alone into one carriage, and we, (with the luncheon) were pushed into another. I believe the poor dears never spoke, but sat, holding each others hands, until we reached Brighton, and to their great comfort, were safe in a fly!!

We had many friends there, though your father would not take a holiday. We rode on horse-back, and on the whole, had a gay time. We hoped to have been married that Autumn or early in 1843, but things did not prosper, and I could not have the small fortune promised by my dear father. I was often away from home, at my three Uncles, or in London with Mr. Fry, and in that year Mrs. Barton left us, and went out to Lima where her husband had been made Consul by Lord Aberdeen. She meant well, and was really a good woman, but rather tiresome, perhaps she found us the same.

In the Autumn of 1843 I again went to Brighton with the George Pearces’, by no means so lively as our party of the year before. Aunt Georges’ daughter Annie Dipnall now Mrs. Carr of Surbiton, and I were friends, and Elizabeth my own cousin was fond of me.

My brother Stewart had been in India for some years, but never doing well, no steady perserverance, and he had married imprudently in every sense of the word [see note]. I was godmother to his boy. I always hoped the poor child was taken from the evil of his conditions, for with so careless a father and so bad a mother, no good could have come to him. William had given up his appointment at the Swan River, and gone to Calcutta to Stewart, hoping for employment in his own profession, but India was not ready for railways, and William could find nothing to do. Your father wrote offering to take him as a clerk in his Office, and if he did well, as a partner ultimately, so he came back to England, and made our house as merry as it had been before he went away. But had we looked forward, and seen the future, we would not have suggested this plan. The business was not a good one for William, who was self-indulgent, like his family, and the loss of an excellent clerk, who was given up to make a place for William, was a great loss to your father. I was seriously ill in the Winter of 1843, and unable to go out, or enjoy any of the gaiety which went on.

Gardener’s Cottage, Under Tulse Hill (John Ruskin, 1835) © The Ruskin Foundation (Ruskin Library, Lancaster University).

At that time we had become intimate with the Trollopes a large family living on the old part of Tulse Hill. After Christmas, Louie and I went to Mrs. Cannon’s at Woodbank, Gerrards Cross for change for me. We were a large party, and had much acting and dancing, with other young people near. Among them were the Charlsleys, the eldest son blind. He has now built Charlsley Hall at Oxford, and still lives. A younger son. Robert married afterwards Margaret Cannon, and they live now at Oxford. Your father and William also came down, it was a pretty place.

In the Spring of 1844 an unexpected circumstance happened. The tenant of our old house in Harper Street, Mr. Berkeley, gave it up and but four years of my father’s Lease was unexpired, so it was unlikely another tenant would be found, it would be a great loss to my mother to lose the rent, and leave it empty, and it was proposed that she should live in part of this large house, with my two sisters and brothers, whilst your father and I would be married, and have all the rooms we required.

The plan arranged was that we had our own servant and took breakfast in our own room, but dine together and be separate, or together in the evening as we liked. A person applied for our house at Tulse Hill and all was soon arranged for our wedding in July. The plan seemed very feasible and good, for all parties, but I having tried this “Happy Family” life, do not think it ever succeeds, unless with people of singular calmness, or possessed with thorough judgment and self-control.

Relations who are deeply attached to each other, and who can cheerfully make great sacrifices on important matters, may easily fail in that power to “Give and Take”, which is always needed in the trivial details of daily life.

We were very busy all that Spring and early Summer. Uncle Charles gave me £100, to buy my trousseau, so I was no expense to my mother, and I was able to do something out of this sum, for all the others. Uncle John gave us also £100, towards furnishing, from which we bought our Piano, and we had many kind and handsome gifts, from the families on both sides and intimate friends. In those days, wedding presents were not the universal tax on every acquaintance even which they are now.

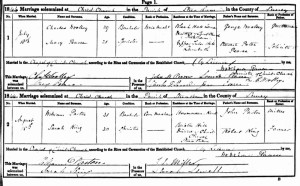

We were married on the 18th July 1844, the same day on which my Grandfather Pearce had married Miss Walker in 1780. Their wedding trip, was to Epping Forest for the day in a Post Chaise! We were to go to the Isle of Wight and see Mr. and Mrs. Woolley ( an Uncle ) at Littlehampton. Christ Church which we had helped in building was to be consecrated for weddings. The Bishop was abroad and there was a delay of the messenger, so the necessary papers arrived only on the morning. The Church was full of people, and little children whom I knew, scattered flowers and sugar plums on the doorway as we left. My bridesmaids were, my sisters, your Aunt Ellen, Fanny Cannon, Elizabeth Pearce, and Fanny Pearce, of these Fanny Cannon and Mrs. Allcard alone survive. We had the ordinary Wedding Breakfast and all our families were there. The cake came from “Walkers” in Piccadilly, who had supplied all for the Queen in 1840.

We posted to Cobham, in a heavy thunder-storm and the postilion had too freely drunk our health, so we were not sorry to find ourselves safe. The next day we went to Southampton, crossed to Cowes, on to Newport, and thence to the Undercliff and Freshwater, it was lovely weather, then we came back to Portsmouth, and Chichester, where Mr. Woolley met us, and we drove to L’hampton, they were very kind, but I felt it very dull, though they took us to Arundel Castle, Goodwood, and other places, making picnics everywhere. Then we went on to Box Hill and Mickleham and so home. This was my second visit to the Isle of Wight, as I may have said before.

*A painting hung in my great grandfather’s house showing an old lady with a bible. When the picture was restored, the bible was revealed to have been painted over the image of a child. Family history suggests that this child was Stewart Highmore Pearce, and that he had been painted over due to his disreputableness. (The painting was later given to the artist Charles Maresco Pearce – both he and my great grandfather William Seymour Eastwood were the children of Mary’s first cousins).

Continue to Chapter Eight: Married life in Harpur St. – Stewart, Bertie, Louie, Duncan, Alice, Grace, Katie and Margaret born – Move to Peckham then Clapton – Scarlet fever, whooping cough, peritonitis etc

Email link

Email link