Chapter Eleven

Return and unsatisfactoriness of Stewart (son) – Cannibals – Move to Woodford – Journey through the Alps for Charles’s health

Almost immediately after our return, our poor Stewart came home from Australia. He had held some post in Japan, but I doubt if he were ever fit for work. He was very ill in China, and had ophalmia with his old malady of internal tubercles, so that he was for a long time in hospital.

The Counsel at Hong Kong, Mr. Hewlett, knew his father, and he went to his house, then to the French Charge d’affaires who took a great liking to him for his abilities. But as he did not recover, a voyage to Australia was advised, and he went to Sydney. On his way, the vessel touched at the Solomon Islands to get sponge and coral. The natives were and are now, very savage and cannibals, a fight took place, and Stewart was hurt in his foot, but mercifully, all got safe to their vessel. On his reaching Sydney, he staid at Mrs. Tom Woolleys, and she and his cousins were kind to him, but he was not prudent and vexed her. After going to various places, he determined to come home, in the hope of regaining his health. He wished to go on with legal studies so that perhaps he might regain his lost chances, so his father arranged he should be placed with our old friend Mr. Blaxland, whose son Athelstan was in his office. Stewart began well and Mr. Blaxland thought he would succeed, but his old weakness for playing billiards over-mastered him, and we were very anxious, as the Spring of 1867 went on, feeling London was unfit for him both physically and otherwise. This added to his father’s cares much, but I knew little of business anxieties then.

At Christmas 1866, Charles had obtained possession of all the block of New Building in Mark Lane, which had been erected on the sites of four old houses, one of which my mother had been born in in 1794.

It was now wholly offices, and the rental gave a profit of £1000 a year. This property was settled on me and seemed a great possession. I recollect I was ill and the deed was brought up into my bedroom at Grove House to be signed and witnessed. This was my first fortune, and like others I have had since, has vanished away.

In May of 1867, Bertie came of age and as Stewart had been absent when his 21st birthday occurred, I wanted to give the children a dance to celebrate both. Just before I had gone to Worthing not being well, and Charles promised to go and rest, but he could not do so.

On May 29th the birthday party took place, and very bright and gay all were, though there was no extravagance or display. Amy was ill at the time.

We little thought the small cloud of care, would soon spread and break, nor did any feel, that this Summer would be the last of ease and comfort.

Stewart’s health grew worse, and though he had not the moral strength to give up the one bad habit which he blamed himself for indulging, yet he was very unhappy, knowing how he grieved us, so he became very worn, and unfit for anything.

At last in August he decided on going out to Canada as Mr. Toulmin hoped a clear, bracing air might arrest lung mischief. But on the 1st September Charles was attacked by severe illness suddenly, we were so alarmed that Stewart went up to London to fetch Dr. Quain, as our doctor feared the worst.

A week of great anxiety followed, but then he began to rally. Stewart had to sail for Canada on the 12th he had been quite ill from the shock of his father’s attack, and his hurry to fetch Dr. Quain and I was so desirous he might not have to go, without having an assurance that his father would live.

He left Grove House at four a.m. on September 12th I had been sitting up all night, and had gone to his room early. He had closed his box and sat down on it to press the lid to, but he was a mere skeleton, and his weight useless for the purpose, he looked so ill. Bertie went to Liverpool with him, and we were able to send better accounts of his father.

Charles’ illness continued some time, and he was unable to go to London. His business affairs had become so complicated, that he only could have arranged them, his absence was therefore ruin.

His friends constantly came down to Grove House trying to carry out his arrangements in business, but he was fit for no work, and change was ordered, so he went to Worthing, for a month having some of the children.

On our return it became needful to retrench in our way of living, that meant to reduce number of servants and have less ground, so we took a house, The Rookery, George Lane, Woodford, where we went after Christmas 1867. It was a smaller place but now I think we had done better had we lived more cheaply in Grove House, until it was let. Charles was not equal to any business cares, or to face all the complications which had arisen since his illness, and Dr. Quain, said if his intellect were to be saved, he must take six months of entire rest in new scenes.

Directly Aunt and Uncle John heard of this, they gave me a cheque for £100, that no anxiety should weigh on Charles’ mind, as to Expenses. Bertie was then 22, and equal to carrying out regular business, and four intimate friends, undertook to superintend all other matters, so that no sacrifice should be made.

On the 27th I think of April 1868, we left home, and eleven children, with every hope of cure for their father. An old lady friend staid at the Rookery in charge.

It was a hard trial to say goodbye and my little Charlie was only 3 ½ years old, we had asked Jane to take charge of him and his nurse, but Mr. Buttanshaw said he would not have a child for six months and then let him go, so he, Maud, the three elder girls and Bertie, were at home, Duncan at Merchant Taylor’s school, living at Woodford, Frank and Basil at Dr. Guy’s where they were able to remain, through the kind aid of our old friend Mr. Jacomb, who when we talked of removing them for economy, would not allow it, saying all would come right in our future.

We went to Folkestone and spent a week at a private Boarding Hotel on the Lees, kept by some old servants of the Toulmins. The weather was bitterly cold, following a hot early April. Such wind and snow I never saw, we could not leave the house, and Charles was most depressed. On the 3rd May, we saw the vessel pass, having Ada Lashbrooke on board, who was going to Melbourne to marry her cousin Fred Austin.

Suddenly came a change, and in a day or two, we crossed over to Calais, in a broiling Summer’s sunshine, and then began the Summer of 1868, of intense heat, and in spite of trouble, it was an enjoyable six months.

The heat was intense during the crossing to Calais, and I had a violent headache when we reached Paris, where we only were to sleep. I went at once to bed, and my husband strolled out, gradually as the cool of the evening came on, I felt better, and when Charles returned, and ordered a slight, tempting repast to be sent to me, I got up and enjoyed it. We had a good night, and were rested by the morning, when we set off really for Switzerland, but I was so afraid he would be over-taxed by the long journey that we settled to spend two or three days at Dijon, to see the Cathedral, which is old and good, and the town quaint but dull. Finding we had taken so much luggage as would incommode us, we sorted out unnecessary articles, packing a box to be returned to London.

To our annoyance, when settling the bill, money had run short, and we had arranged our circular notes for Neuchatel, where we intended to rest for the first time. The faith and courtesy of the Hotel Proprietor soon relieved us. He begged we would feel quite tranquil, and was content to accept Charles’ promise to send cheque from Neuchatel. After leaving Dijon, the heat was great, and Charles so worn out, that a second halt at Macon was needed.

Macon is a very picturesque town on the [Loire] no very high hills, but on level. All the slopes covered with vines yielding a white wine, Burgundy, at that time little known in England. The river is a lovely feature in the landscape, we enjoyed seeing it, and was sorry the train left so early as to allow no time in the morning for another survey.

Alas! How little we then thought how much loss would eventually be ours, through that halt at Macon. We left at 5 a.m. going in the omnibus with a very charming young couple, French evidently of social standing as three servants were with them. We were in the same railway carriage, and after a while, the gentleman offered us fruit, of which they had a fine display, and as they spoke English well, we had some conversation when Mde. Opened the travelling bag and offered me scent, I saw all the stoppers were gold, having a Duke’s Coronet on them.

She told me of her little children in Paris, two, asked me if I went to the Court, when I informed her that all such life was above my rank in Society, although I knew much about it. This in no way checked the pleasant chat, nor that between our husbands; when we stopped and changed carriages for Switzerland.

They were going to the South of France. I saw their names on the numerous packages on the platform, they were the young Duke and Duchess of —-. My memory now fails for the French title which was that of an old family of whom I had read in Lady Blessington’s book the ‘Idler in France’. After a cordial adieu we separated. The next time I saw the name, it was among the killed in the Franco-German War, a sorrow for her, which neither title nor luxuries could heal I fear.

The railway by Pontalier to Neuchatel was then a model of engineering skill, ascending the Mountain in a series of zigzags, so that you could often see the end of the road just travelled, by the side of that on which the train was running.

It was very late when we reached Neuchatel we were both tired and hungry, but had to content ourselves with some poor food, so went cross to bed. All seemed better the next morning on looking over the beautiful Lake and landscape. After a good breakfast we went out to survey and climbed a high terrace I think near the Castle or Chateau. It was a lovely morning, and the sky and clouds perfect. Suddenly, in an extra gleam of sunshine I began to wonder why some distant white clouds, low on the horizon, were so fixed, no movement. In a few minutes the knowledge flashed upon me, that I was looking for the first time on Snow Mountains. The Alps. I seized Charles’ arm and made him also see, and then we sat and gazed upon them in silence. A sensation I believe, only to enjoy once in a life.

Leaving Neuchatel that afternoon for Lausanne we much enjoyed the views of the Lake of Geneva and mountains, we went to Vevey, where we remained two or three weeks, “en pension” at the hotel de . This had been an old family mansion with frontage to the street, but at the back, consisting of three sides of a quadrangle, and gardens going down to the lake. At Neuchatel we had met two sisters, Misses Jago, cousin Miss McAdam, and Admiral Jago the youngest Admiral in the service. They also came to this Hotel, and we became very intimate. After leaving Vevey, we went on to Glion, a place of most lovely views but not many walks, though I always enjoyed the walk down to Montreux, of course, we saw Chillon and its Castle.

In the middle of June the weather became cold, we had settled to go to the “Diablerets as being higher and more bracing when it was so hot at Vevey; but we found it very cheerless there.

The Hotel was almost empty, and no stores of provisions, all stoves had been taken away, and we had to sit in our cloaks and great coats for warmth. Cakes or sweets none, and cooking bad, it was very dull. However, we at last had some sunshine after days of snow, wind and rain, and had one or two scrambling walks. Then we took a car, and with our luggage drove to Sepey thence by Cumballey, where by Mrs. Scott’s advice, we rested and had splendid coffee, on to Chateau D’Oex this was our first experience of driving in a Swiss car, and the headlong pace at which we decended by zig-zag roads from the mountains, always on the edge of deep ravines, was trying to the nerves of invalids. I quite delighted in it, and always chose the outside edge of the seat, so as to have the greatest swing as we turned the sharp corners. I did not do this on a later visit! Chateau D’Oex is a broad beautiful valley on the Lucerne. We went to the Pension Rosat, our first trial of a real Swiss wooden house with balconies, the highest charge was four francs a day on the 1st floor, we could only get rooms on the second, having the same outlook, all were alike fitted with wooden furniture only bedside carpets, the Salon and Salle a Manger lay on the first floor. Our food was excellent and plentiful, compotes of fruit, cream etc., it was delightful, and weather perfect.

After a few more days more people came from the Diablerets, like ourselves, finding that place cheerless. Among these was a Major and Mrs. Mainwaring, she was a daughter to Kelk, the railway contractor. We became friendly, the Major and Charles played chess often. On the third day or rather evening they played to a late hour, the Major had not been very well, and complained of the shaking of the car in coming. About 5 a.m. we were woke by Mde. Rosas begging me to come at once to Mrs. Mainwaring. I hastily drest, and ran down to her, when to my horror, I found her almost distracted, and her husband dead. She had gone to bed late and fallen asleep, waking up and not finding him with her, she had gone to his dressing-room, a closet door was locked, but she could get no answer, and roused the landlord. After some time the door was forced open, and poor Major Mainwaring was found quite lifeless.

A very trying time followed, we were the only English people, except Mr. and Mrs. Parkes who were Roman Catholics, and the widow clung to us. The funeral had to take place at once, but the syndic of the village, extended the time by a day, until the only child, a son at school at Dresden, I think, could arrive. There were no wires nearer than Thun or Beg, and the weather had changed to a heavy snow storm, rendering travelling difficult. However a young clergyman Daniel Powell, whose family we knew, said he would risk it, he succeeded and Henry Mainwaring reached Chateau D’Oex on the Sunday. The funeral was quite primitive, only a wooden coffin, no mourning to be had such as Mrs. Mainwaring wished for. The little church stood on a high rock in the centre of the valley, it had been the Castle and was reached by a 100 steps. We followed as mourners. The rock was so near the surface, that earth could hardly cover the coffin and the straw laid upon it.

All the trouble and anxiety of arrangements had been ours, as poor Mrs. Mainwaring was absolutely crushed, and needed constant care. My husband was so over tasked by it, that I decided on leaving, as soon as the son came and the funeral over. There chanced to be a return carriage going down to Thun on the Sunday afternoon, so we took it, and drove down the lovely Thal to Thun, which place we reached at the close of the Sunday. It was such a peaceful drive, after the sad, exciting days we had passed through, always near the river, rushing brightly under stones through wooded heights, to lose itself in the lake of Thun.

We went to the Pension, —- kept by a Swiss Lady who had married Captain Campbell. The evening was closing, but all looked bright, and when our carriage drew up, we saw on the doorstep, two ladies, one of whom sprang towards us, and we saw it was Hannah Hamilton who had been a sort of governess to our little children and companion to me. She was a nice girl, neice to Miss Hildyard who was the governess to the Royal Children, and who was loved by them till her death.

The other lady was Hannah’s sister, Mrs. Margetson with one little girl. It appeared Major Margetson (of Ditchingham Hall, Norfolk), was not in good health, so they were staying here till he felt better, and they were glad we came. We made some excursions, and the Summer days went by, but the Major did not leave his room, and the Swiss doctor looked grave. At last Captain Campbell spoke to us, and said he feared it would end fatally and begged me to break these tidings to his wife, and Hannah. I did so, and once more, we had to go through all the sorrow we had endured at Chateau D’Oex, only now with friends.

I felt it to be impossible to allow Charles again to go through the trial before us. He had been so shaken by the first, and his health and progress had the first claim.

Mr. and Mrs. Parkes came after us, and they promised to stay on and do all these poor people needed, besides Thun was a larger place and an English Chaplin could be found. Hannah saw the necessity for our going, so with great regret we left them, and went to Interlaken, after a few days we heard Major Margetson had died, and we were thankful to be spared more of such grief. After seeing the Falls at Giesbach, we went up the Lake of Brienz to Meyringen and the weather was so lovely, we went to see the Falls of Rosenluc or the ascent of the Little Scheideck. This first trial of real mountain walking with a delightful Guide, was so pleasant, that he easily persuaded us, to let him go back to Meyringen, fetch two small portmanteaus of clothes, and then cross the Little Scheideck and Wengen Alp to Lauter brunnen.

It was easy mountaining of course, but the air was delicious and the novelty great, the only draw back being the grey flies, which bit through gloves or silk wraps, drawing blood, and being very painful. We descended into Grindelwald as the lights were beginning to show in the houses, and went to The Bear, our guide hastening on to order rooms and hot foot baths as our feet were sore with nearly nine hours of walking.

We went in the morning to see the Glacier, then set off over the Wengen Alp to Lauterbrunnen. The snow was in masses on the summit, but it was melting and we heard the fall of slight avalanches. A bottle of champagne at the Hotel on the top was very refreshing. I have always found the descent of a mountain far more trying than climbing, and I certainly was tired and worn out when we accomplished the long weary path backwards and forwards on the mountain-side into Lauterbrunnen. We were really tired and over done by the hot sun, and I know we were rather cross. I am not sure it was a prudent excursion. Certainly not the way to rest.

We reached the hotel at Brienz late in the evening, weary and hungry, for we were too tired at Lauterbrunnen to eat, to our disgust there was nothing for supper but large veal chops, coarsely fried, half cooked, and we went to bed still hungry and cross. The next day we went on to Meyringen once more to collect our luggage left there when going to the mountain, and crossed the grand Bruni Pass to Lucerne. The road was very fine, no railway then, and the outside of the coach or Diligence was delightful. At Lucerne we went to the Schwann Hotell, which I did not care for, as there was no view. After our first ramble about the town and sitting by its beautiful lake, we decided on going to the Pension Schweilzer, kept by the Bros. Kopt, and remaining there for a good rest, making easy excursions. A letter came from our acquaintance the Misses Jago and their brother, begging us to take rooms for them where we were.

Our rooms were very nice, “Au 2nde” opening on to a wide balcony, and looking over the lake. We always contrived to find 2 rooms with door between, one always had a prospect, so we had the two beds moved into the less pleasant one, slept in it, and used it for my dressing room. Charles drest in the other, which we arranged as a sitting room also, and sat there after breakfast. The furniture of such rooms was simple in those days, wooden bedsteads, no curtains, table, chest of drawers with toilette glass and small washstand. We soon got into the way of taking a Siesta after the early meal at 1.p.m. there was always a sofa in each room, so we rested peacefully, until it was cool enough to go out. In those days, no afternoon tea was to be had, but the Jagos and ourselves were provided with tea brought from Home, so we usually joined forces about 4 p.m. thoroughly enjoying our “Cups” though it often was a very picnic affair, it was always merry. We always continued this tea-making and at other places gave pleasure to any nice person when inviting them to share it.

We had simple breakfasts, about 8.30 to 9 a.m. going down when drest, then a good stroll, or a steam boat excursion. Lunch (or early dinner at 1), then rest and letter writing or reading if not done before 1, tea, a long walk. Supper of cold meats, vegetables, sweets compotes, and fruits, afterwards we sat out of doors… Sometimes musicians came and a concert was given, or some played cards, occasionally the young ones danced. We took the usual excursions to Brunn and Fluellen saw William Tell’s Chapel, though his story is now called only a myth, and were never tired of the beautiful Lake Scenery with perpetual variety of coloring on hills, lake and mountains. The bridges too were so picturesque, one all painted on the sides of its wooden roof with Holbein’s Dance of death. Lucerne too had some very quaint and picturesque towers and fountains. One of my occupations I had forgotten, namely making pencil sketches of these views and buildings. I succeeded much better with the last, as views are too extensive for unprofessional artists.

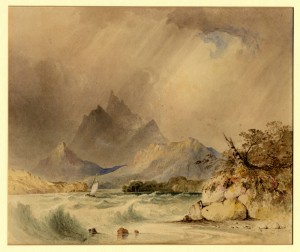

Mount Pilatus by John Ruskin, 1835/6, © the Ruskin Foundation (Ruskin Library, Lancaster University)

The weather was very fine all that end part of June and July in which we staid at the Schweitzerhaus and at last, we were seized with an intense desire to walk up to the top of Pilatus, sleep there, and see the Sun-rise. Admiral Jago wished to join us, which pleased me, as I liked him, and I knew he would help Charles if tired. All the people in the Pension opposed my going, but I would not let my husband go without me. So one fine afternoon about 3p.m. we started. For some distance the road ascended through orchards then some “Green Alp”, and later on, steep rocky paths, rather tiring, the top is I think about 7,000 feet, but there was one part of the climb steep as on the ‘Little Scheideck’ Admiral Jago did help me. not Charles, for I was rather tired when we reached the top. Being early in the season, there was a bad supply of food, and I am inclined to think the beds were damp ! but we were tired ! and went to bed early, and I was told the two gentlemen slept, but after I had exhausted my first short sleep, I became so excited by the fear of being too late for the sunrise, that I perpetually made a journey to the window, looking for the dawn.

It was decidedly in advance of that time, when I could bear no more delay, but waking Charles, and going outside to call Admiral Jago, we drest and prepared to go up the few hundred feet, remaining to the summit, that was a climb indeed, near the top, the ascent is made through a chasm piercing the rock, a natural one, in which a ladder is laid across, and you have to creep along the rungs of it, on hands and knees, and the passage is so low. When we reached the actual top, we stood looking down on Lucerne at our feet, it was a grey morning, no sun, and we feared no view, the valley below us was piled with masses of cloud, and these appeared to us as though the whole space on which we gazed was filled with masses of white cotton wool. Suddenly, as the sun rose over the peak of the mountains and his rays fell into the Valley, this enormous mass of soft white cloud, drew upwards, and slowly vanishing gradually disclosed all the Lake and its beautiful borders, the town and tbe buildings lying at our feet as a picture!

We stood silent, just looking, watching the changes in the landscape as the sun rose, and feeling we had seen one of the loveliest and most wonderful scenes possible.

After scrambling back to the Hotel and having a proper breakfast, we began the walk down, and as before, it tired me far more than ascending, it was nearly 4 p.m. before we entered the hall of the Schweitzerhause, and all in the Saloons hurried out to greet us, and condole on the dreadful fatigue we had under gone in walking up. We were very cheery, assured them we were not tired, and I ran upstairs to my room saying the walk was easy to English people! However, when I tool off my Alpine boots and stockings all the nails on both feet were dark purple, almost black, from the pressure downwards in the descent.

We remained at Lucerne through July, not doing much after Pilatus as weather was intensely hot. At the close of July, we began our progress to Wildbad, where Charles had by Dr. Quains’ orders, to take a course of baths. On leaving Lucerne we went up to Schaffhausen, and by my wish took rooms in the Chateau Lauffen, the old baronial residence close to the magnificent Falls, our rooms overhung the water – alas! My mistake was evident as soon as we settled in for the night, as sleep was utterly impossible close to the thunder of the huge mass of the water, it was deafening, one only implored it might cease if but for a time, but no! On and on went the mighty roar and if utterly tired, sleep came for a few minutes, it was only to wake to the full consciousness of its being worse than before.

In the morning early we got up, weary and worn, it was a wet morning, and after breakfast, we put on the usual waterproof garments and went out in a boat to a rock under the Falls, and then we realised the perfect majesty of the sight, fortunately the sun shone, and in our great wonder and delight, we forgot our weariness and loss of a night’s rest. I made a little pencil sketch of the tiny bridge which crosses the river. We went on to Baden in very bad weather and the town was so full we could only get rooms with a parapet wall before the windows so we could see nothing but the rain, it was dull. At length we took a fiacre and drove to the Chateau, a very ancient Castle, at first the porter doubted if we could be admitted as the Royal family were there. Just then an officer passed us, he stopped a moment, and when he had gone, we were told it was the Crown Prince, Frederick William the father of the Duchess of Baden, and who afterwards succeeded his brother as King of Prussia afterwards becoming the first Emperor of Germany in 1871.

We saw all the antiquities of the Schloss and its dungeons which were used by the Vengetts or Secret Council. The Oubliette, a deep well, in which persons who had been tried, were led over, when the ground fell under their feet and they fell in, the sides all covered with sword blades. Also the Rack, and other instruments of torture. We went into the rooms now used by the family, at the entrance to the Salon, an attendant courteously asked us to pause, whilst he asked if we might go in. A lady’s voice said we could do so, so we walked in, finding ourselves in the presence of the Grand Duchess, her mother the Crown Princess of Prussia, afterwards the Empress Augusta.

We made a suitable obeisance and retreated, other ladies were there all working, on our way out we again saw the Crown Prince. In the evening we visited the Kursaal and saw the gorgeous Salles for reading, music and gambling. The season was early, so not many people were there, only two or three tables were crowded. I watched the roulette and rouge et noir tables, it looked like a child’s game, and I half wanted to try my luck, but Charles would not.

Continue to Letters

Email link

Email link