Chapter Six

The case of the missing hair – Move to Cheshunt and back to St Swithin’s Lane – Engagement – A near riot

For nearly two years my brother Stewart had wearied of the study of the Law, and had caused much care to all, as he was wild to go to sea, besides getting into trouble by his idleness. My mother would not consent, and I was dreadfully grieved, as I so wished him to succeed our father. However, it was useless. A friend of Edward Bean, who had been 1st Officer in an East Indian Ship, was taking out a beautiful small schooner for the opium trade in China. He offered to take Stewart, and all hoped one voyage would cure his fancy for the sea. He was 17, too old for the Navy.

All was thus unsettled at home. Miss Silberred said I was far beyond her control, and wished to leave, so it was arranged for Louie and Jane to go to school at the Miss Jones’ at Stratford, whom we had known when there, old friends of the Loxleys. I was to stay at home, and carry on my education with masters. Now I can see what a delusion and mistake was this scheme. At Michaelmas 1836, my sisters went to school, and Stewart sailed for China in the “Ann” with Captain Pylus.

At the same time my father, mother, and I left London for Dover, where we were to spend a few weeks, in order to try and forget the sorrow of Stewart’s trouble. I never passed through so dull an experience. My poor mother hardly ever spoke, but worked at her Berlin wool work incessantly. The house we were in was on the harbour, to amuse my father with the shipping, far from all the gaiety and fashion of the place. I really had nothing to amuse me, and found it very hard to study in the way my dear father thought proper. Every afternoon we drove out in a post chariot with postilion, always in the country, and it seems to me it always rained. I sometimes went in the “Rumble.” But papa objected to my taking a book, as I ought to look at the country.

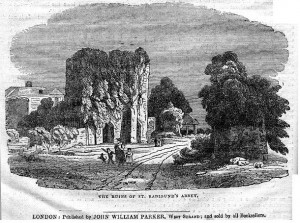

To my delight at last, Aunt Eliza Wicksteed came to stay, then our drives were more exciting, as she was not nervous like my mother. One day the postilion said he knew of some very curious ruins, but the road was awful. We went, and found St Radagunda Abbey, in the midst of ploughed fields. It was built by the Conqueror in the 11th Century. The postilion took the carriage through a gate on leaving, and suddenly found we were at the top of an almost straight descent. He could not stop the horses, but shouted to me to “hold fast”, and in a moment, I saw the heads of the horses were on a level with my face. They literally “sat down” and slid all down the precipitious bank of hill. When we reached the bottom, they stood trembling, for the carriage had been on their backs all the way, and the postboy’s wig which he took off to wipe his head, was dripping wet. He said, had he not been obliged to bring a pair of most powerful horses which we had never had, a terrible accident would have followed.

Very few people ever heard of St. Radigunda’s Abbey.

Sometimes we drove to Folkestone, then only consisting of a narrow steep street of cottages, fishermen – they were ostensibly smugglers really. The only good house was the Rectory, where our friend Mr. Pearce was rector. He was not related to us, but had been a schoolfellow of my father’s. The people liked him, and he had to ignore the smuggling, but many a keg of brandy found its way over the wall into his garden, or a parcel of fine tea, or some French lace for Mrs. Pearce. No-one who knew Folkestone then, but must marvel at its growth.

Soon after we went to Dover, a storm came on, and in a day or two, we settled to drive to Deal to see the waves. Whilst standing admiring their vast volume, on the beach, a sailor said, “Look Sir, there’s a tight little craft as had had to beat back into the Downs.” My father asked her name, and the sailor said, “She’s the Ann, Sir, a schooner no bigger than a yacht, for the opium trade.” Then we knew that Stewart was close to us, and I implored Papa to go out to her. Poor mother was distracted, she could not go for she was a coward on the water, and indeed on the land, and the sailors said it was far too rough to venture. However, I would not take a refusal, and Papa wanted to go, so he offered a sovereign to the man, who accepted it. We were wrapt up in oil-skin coats and hats and went. I was in ecstacy, as I had never seen such a sea. Presently we reached the Ann, and got close to the Bowsprit, when the sailors shouted “Ship Ahoy”, and as I looked up, I saw my dear old Stewart, standing in the chains of the Bowsprit. I always wondered my shriek of delight did not make him drop off into the sea. He dropt down into our boat which tossed dreadfully. The Officers came to the bulwarks to greet us. Only ten minutes talk and hugging each other, and then the order to return. It was a painful pleasure, and with very sad hearts, father and I reached Deal beach. All the while we were away, poor mother had been shedding torrents of tears, for Stewart was her eldest and very dear son, so it was hard not to see him. Many a worse heartache came later on through him, but “at evening time” just a ray of light.

At last the stay at Dover ended, and we went back to Harper Street. Some difficulty arose about Masters for me, and I was not very well, therefore I was sent to Miss Jones’ school at Stratford, where my sisters and the Earles were at school, for a half quarter to Christmas. I was to be a “Parlor Boarder”, that is to sit in the drawing room in the evening, and take supper with the Miss Jones and our former governess, Miss Sherer, who was their assistant. I don’t think these distinctions were good for me, though I highly appreciated them then.

A very curious event took place which even now, after all “clairvoyance” was made clear, still remains a puzzle to me. My two sisters had a small bedroom together the upper floor. I slept with three others, in a larger room downstairs, where each had their own bed. One morning as I was dressing, someone rushed in crying, “Oh, Miss Pearce, go up directly to your sisters”. I rushed upstairs, not a little alarmed, and found their room full of mistresses, girls and servants. Both Louie and Janey were in a bad state, crying bitterly, and on seeing Louie, I cried out. All her beautiful long hair, which fell in loose curls, was gone, cut off close to her head, she crying in terror and several accusing Janey of having done it. Not a vestige of hair was to be seen. By degrees the room was cleared, and some account was extracted from the poor little girls. It appeared Louie had gone to Miss Sherer on the previous evening, to borrow a pair of large scissors, to cut off some frayed pieces from the hem of a garment. The scissors were not to be found, and as all enquiries increased, the agitation and excitement of my sisters, all speaking was forbidden. Search was made everywhere for the hair, in vain, and at my request our parents were sent for. They came down and were very distressed, but no clue was obtained, and Louie who was very delicate, was by this time so ill, my mother took her home. The subject was quite “taboed”, and supposed not to be spoken of.

Some time elapsed when the bed furniture of my sisters’ room was to be changed. It was what we call a “Tester bed” four posts and a dome top covered with dimity. On taking off this dimity top, a parcel fell heavily to the floor. It was the hair. Each long lock carefully lad in a white handkerchief, all in order, the scissors placed on them, and the corners of the handkerchief folded closely and neatly over all. The packet was put on the flat piece of the top of the bed at such a distance from the edge, as would seem to be far beyond the reach of a child 11 years old. So it was however, the commotion in the schoolroom was so great at this discovery, but the opinion about the person who did it, remained divided.

We spent Christmas of 1836 at Harper Street, and my sisters went back to Miss Jones. We sadly missed our brother Stewart, the first absentee from home. I did not go back, as my father was not very well, and his brothers advised him to live in the country, and only come to town two or three days in a week. I used to go distances with him to the country to look for houses, usually driving in one of the high cabriolets which I enjoyed. A house was found at Cheshunt in Herts, chosen as being near to the sea so that my father could fish. Mama and I did not like it, as we wanted to go South of London.

I have the picture of the house at the back, which is nice, a garden going down to the fields and looking over the hills. The front was on the village street, red brick, and old-fashioned, built out with modern rooms to the garden. It had a court-yard and stabling at the side. We removed at the end of March 1837, having let our London house to Mr. Berkeley, whose daughter afterwards married my Uncle Jonathan Barton. There were a few nice people about, all elderly I consider, but we had a bright summer, as our own old friends or relations came to see our new place, and we had visitors always. Haymaking parties, etc. Our old friend Mr. Wislinghausen too, came from Cambridge and charmed Aunt Bean and Aunt Ann who were also with us.

In the Autumn my parents, Louie and I, drove across the country of Herts, via St. Albans, to Norcott Court, near Great Berkhamstead to Mrs. Loxley’s our old friend Mr. Fry’s sister-in-law, where I staid some time with Margaret Loxley, whom I knew at Stratford when a child. My parents went on to Broadstairs with Louie very soon after we returned to Cheshunt (1837). My brother Stewart came back from his first voyage. I had not named the accession of our Queen on 20th June of this year, on the death of her uncle, William IV. She was of age in May 1837.

In November of this year, we drove up to London one morning and long before reaching the City, noticed the smell of fire, at the Green Dragon Inn. Stewart, who had been staying in London met us. His appearance was that of a sweep. He soon explained that the Royal Exchange, built by Sir. T. Gresham in 15(?) had been burnt down the night before, and he, with a number of gentlemen had been helping all night in extinguishing the flames. The present building dates from 183(?). Stewart went to sea again early in 1838.

In the course of March a small dance was given by our friends, the Auberts at Cheshunt, and they so pressed my mother to bring me, that spite of my being so young, 15 ½, she did take me. And as I was well dressed, I passed for “being out” and had many partners. In a few days, Mr. Aubert met my father in the stage coach, and complimented him about me, adding that his eldest son, begged to be allowed to visit more intimately at our house. My father was so vexed at such an unlucky result of my dance, that he at once decided I should be sent to school, and though I implored him to change his mind for once, he refused.

Accordingly after Easter, I and my sister who were moved from Miss Jones’ at Stratford, went to school at Wood End House, Hayes, near Uxbridge. Dr. Beasley had bought the place, and established a girls’ school, under the charge of a Mrs. Thomas whose family had lived at Peckham. It was a fine old house, in large grounds. It is now enlarged, and is a Home for dipsomaniacs. My mother and Mrs. Fry took us down to Hayes, in a carriage. I was never so wretched before. Of course, I was again a Parlor Boarder, and we three had a bedroom together. I determined to make no friends, and to learn everything I could, so that my father should let me come home soon. I soon had a following among the little girls, who lived to do anything for me, and there was only one of my own age, a Miss Palmer of Dorney Court, with whom I chose to associate. The teachers liked me, but otherwise I was very unpopular. At Midsummer, a great party was given. My parents drove over, and we were to go back with them after all the performances were over. It was late and our carriage large and heavy, so at the last stage we had four horses, much to my father’s annoyance, and our delight. The gate-keeper at “Theobald’s”, Sir H. King’s place, had to be asked to let us drive through the park. Papa hated its being so talked about.

In June of this year Queen Victoria was crowned. I went to London, and my Uncle, Mr. Wicksteed, of the “Spectator” took me to see all. We saw the procession going and returning from the Coronation at Westminster Abbey, and in the evening we walked all over the West End, to see the grand illuminations. On the following evening, I went for the first time to the Italian Opera House for the Special Performance. It was an awful crush getting in. The House was crowded throughout, and ladies wore their splendid Coronation dresses and plumes. “God Save the Queen” was sung. It was a fine sight.

In November 1837, I had been at a house in the Strand to see the Procession of the Queen going to the Guildhall to dine with the Lord Mayor and Sheriffs of London. Enthusiasm was at its height, and the shouts and glad cries of the masses of people attender Her Majesty along the whole route. We could not get away till after the return of the Queen. I remember it was too late for me to return to Cheshunt, and I had to sleep at 10. St. Swithin’s Lane.

I left Hayes at Christmas, after only nine months studying, and was only 16, but my father was not well, and wished me to be at home. In the spring of 1837 Mr. Cannon had married our old friend Miss Loxley, and they all lived in her house at Stratford Green.

I omitted saying that when I came up from Mrs. Loxley’s Norcott Court, in 1837, I had my first experience of a railway, then the wonder of the age, coming by the L.N.W.R. from Great Berkhamstead. This railway had only been opened that year, at the grand ceremony of opening. Between Manchester and Liverpool a sad accident occurred. Mr. Huskisson, an M.P. and a very able man, had left his seat in the carriage, to speak to the Duke of Wellington. By some mischance, the train moved, and an open door struck Mr. Huskisson to the ground. He died almost immediately. His wife, I think, was in the train.

Early in 1839, March, my father gave up living at Cheshunt as the long coach drive to London and back was too fatiguing for him. He had not found a house to suit, and determined to put our furniture etc., into the three upper floors of his house, 10, St. Swithin’s Lane, for a time. There was ample space for us, as Stewart was at Sea, and William was articled to Mr. Thomas Wicksteed, a civil engineer, and lived at Old Ford in my Aunt Eliza’s care.

In August 1837 I was invited by Uncle and Aunt John to go with them, Aunt and Uncle Charles, and their eldest boys, William and Charlie, to the Isle of Wight. Such an excursion was considered real travelling in those days. We went in Uncle Charles’ carriage, a large landau, the four old people, as we thought them (none over 40 to 50) and we three on the wide low Coach box, a pair of horses with postillion. We set off early on a very hot morning, and reached Guildford to lunch. The elderlies were knocked up, but I was allowed to take my little cousins into the quaint, old High Street, so beautiful then, since so altered though not quite spoilt. We saw Abbot’s Hospital and the Castle and Trinity Church. Afterwards in the cooler part of the day, we drove over the grand Hog’s Back, by the Devil’s Punch Bowl, to Winchester, where we slept at the “George”. I was awakened about 4 a.m. by military music, and saw a detachment of soldiers leaving the city. We saw the grand Cathedral and Great Cross, then to Portsmouth and slept, saw the Dockyard and the Victory, then crossed over to Ryde, where we spent Sunday. We saw all the Island, then a lovely garden and full of charming villas, houses and sweet scenery.

When we reached Freshwater Hotel, there was only one bedroom, two beds. This was assigned to Uncle and Aunt Charles, and the boys and we heard that two nice bedrooms for us were to be had in a cottage close by. When we reached it at night, it proved to be a mere whitewashed hut, with one room on the ground floor, and over it two lofts which were reached by a step ladder against the wall through a trap door. My Uncle was six feet three inches high and he looked as if he could put his head in at the trap; my Aunt portly. I shall never forget our ascent, and when we reached these lofts (there was no door between). The only furniture was a truckle bed with a rough mattress on it, a chair, and a basin and jug on a box. It was dreadful for the others, and I dare not make it a joke, as it was earnest to elderly people. However, we endured it, and we had a very enjoyable ten days. I was considered very lucky in being one of the party.

Nothing evidences so plainly to me the changes in London, E.C. in the last sixty years, so much as the fact that young girls could then live in the very heart of the city, walking out regularly, without a chaperon, as we did for two years then; now the crowded street would be impossible for us. It was always healthy too, and plenty of air.

Very soon after we came to London in 1839, I was confirmed at Christchurch, Newgate Street, by the Archbishop of Canterbury. Old Mr. Watkins, Rector of St. Swithin, London Stone, (who had married my father’s mother) examined me very kindly. I was very troubled that he might expect me to say I would renounce all the amusements of the world, Dances, theatres, etc. This was told him, and he said to me “Act according to your conscience in all these matters, and I earnestly pray, my dear child, that you may be led to value higher things so much, that you will, of your own desire, turn from all mere worldly amusements which would keep you from God.” And the good old man was right.

We did not go out of town that summer all together, but all paid visits, and often went to concerts and the theatres, and had a great many visitors. Mr. and Mrs. Fry took me once to the English Opera House when the young Queen was in the box opposite to us. A gentleman of the party, took me up into the corridor leading to her private entrance. It was empty, and when Her Majesty came from her box, followed by the ladies and some gentlemen round her, she stood still, close to me, whilst being wrapped in her cloak. I had a delightful view of her, and curtsied. She was quite simply drest, no ornament on her fair hair. She looked so young and small, but had the bearing of very high rank.

In the winter I went to my first public ball, at the Albion Hotel. It was given in aid of a charity, and got up by the Tilson family. I wore a white satin dress and white flowers round the plait of hair, worn low at the back of head, and banded off my face above my ears. This was my fashion after seeing Mde. Grisi at the Opera. I danced all the evening.

In 1840 my father decided on living permanently in St. Swithin’s Lane, and going away in Summer. Many young men came to our house, and in April I was asked by our old friend Charles Woolley to become his wife, I was too young I think to have decided, but I knew him so well. We were not to be married till I was 19, but we little thought of impending changes. In the early Summer I went once more to Norcott Court, and Charles came down with William. But my engagement did not please the family on personal reasons of their own. In August we all went to Margate for two months, whilst our house was renovated and all thoroughly decorated.

I have recollected that in 1840, June, when we lived in 10, St. Swithin’s Lane, the railway from Fenchurch Street to Blackwell was opened. It was at first propelled by stationary Engines with an endless coil. My father’s firm were Solicitors to this work, and a huge luncheon was given by the Directors at Blackwell, to which my sister Louie, William, and our father went. The line was on such valuable ground, that only just space was left between the crowded houses in a low neighbourhood and in many houses, tiles had been removed from the roofs, allowing a ‘head’ to come through, to see the sight. My Uncle Charles and his family was there and with the great people was the celebrated Daniel O’Connel, the Irish Agitator. My Uncle John had been intimate with him on the matter of the Irish Encumbered Estates, and had staid with him in Dublin, as he visited my Uncle in London. Twelve hundred persons sat down to lunch, and speeches were made and healths drunk.

At last Dan. O’Connel wished to speak and began, but he was very unpopular with all the respectable class in England, and many voices were raised to silence him, but opposition was delight to the Irish orator who persisted, and the riots increased. Very soon missiles were thrown, rolls of bread, cold fowls, pieces of meat, and friend “Dan” simply roaring with laughter, shouting his jokes and taunts. At last it was feared that more serious missiles would be used, such as glasses or knives. Decanters were seized up, a large number of gentlemen forcibly took hold of O’Connel, whose powerful figure and height, rendered force difficult, but at last by surrounding and pushing, they got him down the stairs on to the station yard amidst the yells and fighting of his opponents. To attempt getting him into a train was not safe. Several Steam Boats which had brought the guests, were alongside of the Pier, and after a while his body guard, had him on board, and out of reach of his enemies. He stood high up on the bows of the Steamer waving his hat in wild delight, and sending his jokes and ridicule in a stentorian voice till out of sight. Uncle Charles taking him in charge.

Of course, Charles spent his holiday with us, and our dear old friend F. Wistinghausen was also there: he staid at Dr. Hoffman’s whose widow died lately at West Hill. He and Charles had been rather formal together, but now they became friendly. One day when bathing, F.W. lost all consciousness, and would have been drowned but Charles supported him to a life-buoy, where he held him up, until a boat came out. It was heart failure then.

My father was much on the water, he had favourite boat men. One morning we went out and father said, “Where were you Collins, yesterday evening when I came down?” “Why Sir,” he said, “I had a queer customer last night. There has been a Gent for a day or two at the Royal, and I daresay you have often noticed in your good Glass, a large foreign ship, lying on and off lately?” This my father, and all of us had seen by our large telescope. “Well Sir, this Gent,” said Collins, “came to me and said, could I be ready at 10 p.m. to go off, as he and another Gent, had to go aboard a vessel, dropping down Channel, which would not come close in. Of course we said we would go, as he offered good pay so at 10 p.m. the two came down, and we asked which way the vessel would come. To our surprise he said, “We are going on board the French vessel, which has been off here a day or two. It was not our business to ask questions so we took them alongside of the French ship. A number of men were waiting at the side, speaking French. Our money was paid, and something over, it was getting light and they weighed anchor at once and sailed off. We got back that morning.” We were greatly excited at hearing this strange story. In a few days the mystery was solved. The two men were Prince Louis Napoleon, and a friend, who were going to attempt to raise the Prince to the throne. But, for the moment, the scheme failed, and instead, he was seized and lodged in the fortress of Ham. After some years he escaped and returned to England. In the Chartist Riots in 1848 he was sworn in a Special Constable, soon after Louis Phillipe abdicated, and Louis Napoleon began to climb the steps to the Imperial Throne, which was to end in an exile’s grave in England.

We came back to Swithin’s Lane in October, and had a gay Autumn, all our friends on both sides, making up parties for Charles and me. I had one trouble, however, our old friend Mr. Wistinghausen was in London, looking for work, and was constantly at our house. I was fond of drawing and he procured me a bust of a heathen god, and used to teach me to draw from the model. One day in November he came and some of us went to walk on the Iron Bridge at Southwark, which being a toll bridge was quiet. He left to go to a dinner, and afterwards to the Theatre, with Professor Partridge’s family, asking me to be ready for a good lesson the next day early. I had arranged my materials and was waiting for him, when my father came upstairs, looking very sad. He had just been told that our dear Fred Wistinghausen had passed away in his sleep. He went to bed quite well. In the morning they found him lying peacefully, his arms crossed, quite dead. We all grieved for him, and I think Charles missed him very much. He had grown to like and understand him, and did not then resent my great affection for him which I had from a child entertained.

About two weeks before this Christmas, 1840, (The Queen had married Prince Albert of Saxe Coburg and Gotha, in February and the Princess Royal, now the Empress Fredrick of Germany had been born in November). My father had a serious talk with me as to Charles going often with us to the theatre, an amusement he had given up on conviction, before we were engaged. Papa said he felt our example led Charles to turn back to the world, and he said, he also was feeling we were leading too worldly lives. He spoke of my confirmation the year before, and my doubts then, and also of the Sacrament of the Lord’s Supper, which he said he and my mother had not regularly received, and therefore I had not done so. He asked me to think over this, and be sure that my influence over Charles was a right one. I never forgot this talk in father’s old office. He was always so gentle and sweet to me, and it was our last. Charles said father was right about him, and we decided to resolve to make a change. In a fortnight after that talk, I had no father left on earth.

Continue to Chapter Seven: Death of Mary’s father – Theft and court case – Paris – Move to Tulse Hill – Marriage

Email link

Email link